Giving Compass' Take:

- Vivian R. Underhill and Lourdes Vera explain lobbyists got fracking exempted from regulation under the Safe Drinking Water Act, with consequences for Americans' health.

- What role can you play in protecting Americans from unsafe water?

- Read about the millions of Americans who lack access to clean water.

What is Giving Compass?

We connect donors to learning resources and ways to support community-led solutions. Learn more about us.

From rural Pennsylvania to Los Angeles, more than 17 million Americans live within a mile of at least one oil or gas well. Since 2014, most new oil and gas wells have been fracked.

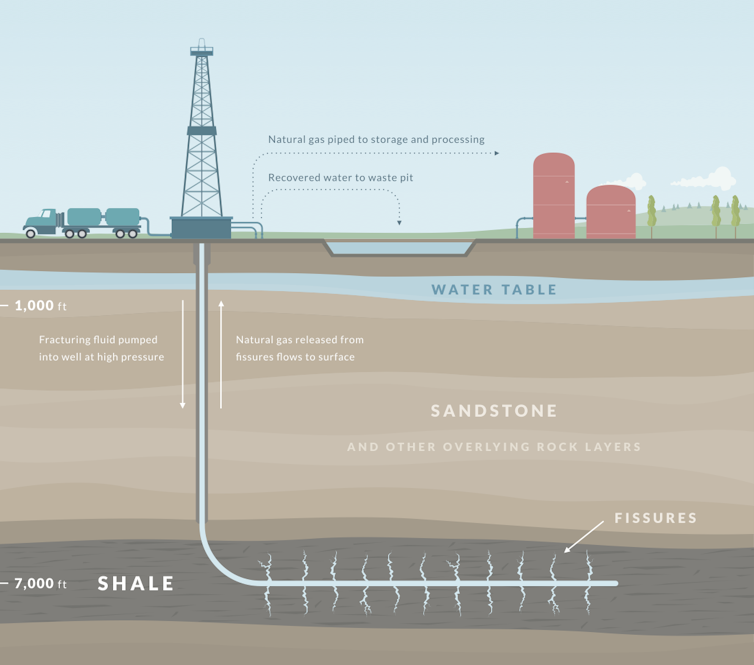

Fracking, short for hydraulic fracturing, is a process in which workers inject fluids underground under high pressure. The fluids fracture coal beds and shale rock, allowing the gas and oil trapped within the rock to rise to the surface. Advances in fracking launched a huge expansion of U.S. oil and gas production starting in the early 2000s but also triggered intense debate over its health and environmental impacts.

Fracking fluids are up to 97% water, but they also contain a host of chemicals that perform functions such as dissolving minerals and killing bacteria. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency classifies a number of these chemicals as toxic or potentially toxic.

The Safe Drinking Water Act, enacted in 1974, regulates underground injection of chemicals that can threaten drinking water supplies. However, Congress has exempted fracking from most federal regulation under the law. As a result, fracking is regulated at the state level, and requirements vary from state to state.

We study the oil and gas industry in California and Texas and are members of the Wylie Environmental Data Justice Lab, which studies fracking chemicals in aggregate. In a recent study, we worked with colleagues to provide the first systematic analysis of chemicals found in fracking fluids that would be regulated under the Safe Drinking Water Act if they were injected underground for other purposes. Our findings show that excluding fracking from federal regulation under the Safe Drinking Water Act is exposing the public to an array of chemicals that are widely recognized as threats to public health.

wetcake via Getty Images

Averting federal regulation

Fracking technologies were originally developed in the 1940s but only entered widespread use for fossil fuel extraction in the U.S. in the early 2000s. Since the process involves injecting chemicals underground and then disposing of contaminated water that flows back to the surface, it faced potential regulation under multiple U.S. environmental laws.

In 1997, the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that fracking should be regulated under the Safe Drinking Water Act. This would have required oil and gas producers to develop underground injection control plans, disclose the contents of their fracking fluids and monitor local water sources for contamination.

In response, the oil and gas industry lobbied Congress to exempt fracking from regulation under the Safe Drinking Water Act. Congress did so as part of the Energy Policy Act of 2005.

This provision is widely known as the Halliburton Loophole because it was championed by former U.S. Vice President Dick Cheney, who previously served as CEO of oil services company Halliburton. The company patented fracking technologies in the 1940s and remains one of the world’s largest suppliers of fracking fluid.

Fracking fluids and health

Over the past two decades, studies have linked exposure to chemicals in fracking fluid with a wide range of health risks. These risks include giving birth prematurely and having babies with low birth weights or congenital heart defects, as well as heart failure, asthma and other respiratory illnesses among patients of all ages.

Though researchers have produced numerous studies on the health effects of these chemicals, federal exemptions and sparse data still make it hard to monitor the impacts of their use. Further, much existing research focuses on individual compounds, not on the cumulative effects of exposure to combinations of them.

Chemical use in fracking

For our review we consulted the FracFocus Chemical Disclosure Registry, which is managed by the Ground Water Protection Council, an organization of state government officials. Currently, 23 states – including major producers like Pennsylvania and Texas – require oil and gas companies to report to FracFocus information such as well locations, operators and the masses of each chemical used in fracking fluids.

We used a tool called Open-FracFocus, which uses open-source coding to make FracFocus data more transparent, easily accessible and ready to analyze.

We found that from 2014 through 2021, 62% to 73% of reported fracks each year used at least one chemical that the Safe Drinking Water Act recognizes as detrimental to human health and the environment. If not for the Halliburton Loophole, these projects would have been subject to permitting and monitoring requirements, providing information for local communities about potential risks.

In total, fracking companies reported using 282 million pounds of chemicals that would otherwise regulated under the Safe Drinking Water Act from 2014 through 2021. This likely is an underestimate, since this information is self-reported, covers only 23 states and doesn’t always include sufficient information to calculate mass.

Chemicals used in large quantities included ethylene glycol, an industrial compound found in substances such as antifreeze and hydraulic brake fluid; acrylamide, a widely used industrial chemical that is also present in some foods, food packaging and cigarette smoke; naphthalene, a pesticide made from crude oil or tar; and formaldehyde, a common industrial chemical used in glues, coatings and wood products and also present in tobacco smoke. Naphthalene and acrylamide are possible human carcinogens, and formaldehyde is a known human carcinogen.

The data also show a large spike in the use of benzene in Texas in 2019. Benzene is such a potent human carcinogen that the Safe Drinking Water Act limits exposure to 0.001 milligrams per liter – equivalent to half a teaspoon of liquid in an Olympic-size swimming pool.

Many states – including states that require disclosure – allow oil and gas producers to withhold information about chemicals they use in fracking that the companies declare to be proprietary information or trade secrets. This loophole greatly reduces transparency about what chemicals are in fracking fluids.

We found that the share of fracking events reporting at least one proprietary chemical increased from 77% in 2015 to 88% in 2021. Companies reported using about 7.2 billion pounds of proprietary chemicals – more than 25 times the total mass of chemicals listed under the Safe Drinking Water Act that they reported.

Closing the Halliburton loophole

Overall, our review found that fracking companies have reported using 28 chemicals that would otherwise be regulated under the Safe Drinking Water Act. Ethylene glycol was used in the largest quantities, but acrylamide, formaldehyde and naphthalene were also common.

Given that each of these chemicals has serious health effects, and that hundreds of spills are reported annually at fracking wells, we believe action is needed to protect public and environmental health, and to enable scientists to rigorously monitor and research fracking chemical use.

Based on our findings, we believe Congress should pass a law requiring full disclosure of all chemicals used in fracking, including proprietary chemicals. We also recommend disclosing fracking data in a centralized and federally mandated database, managed by an agency such as the EPA or the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Finally, we recommend that Congress repeal the Halliburton Loophole and once again regulate fracking under the Safe Drinking Water Act.

As the U.S. ramps up liquefied natural gas exports in response to the war in Ukraine, fracking could continue for the foreseeable future. In our view, it’s urgent to ensure that it is carried out as safely as possible.

Vivian R. Underhill, Postdoctoral Researcher in social Science and Environmental Health, Northeastern University and Lourdes Vera, Assistant Professor of Sociology and Environment and Sustainability, University at Buffalo

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. The Conversation is a nonprofit news source dedicated to spreading ideas and expertise from academia into the public discourse.