Giving Compass' Take:

- Ernest Agee explains how climate change is shifting the paths of hurricanes even as they become more frequent and intense.

- What role can you play in helping communities prepare for tornados to come?

- Read about how to support long-term recovery in tornado-hit communities.

What is Giving Compass?

We connect donors to learning resources and ways to support community-led solutions. Learn more about us.

Tornadoes tore up homes in New Orleans and its suburbs and were reported in communities from Texas to Mississippi and Alabama as severe storms swept across the South in late March 2022. We asked tornado scientist Ernest Agee to explain what causes tornadoes and how the center of U.S. tornado activity has shifted eastward from the traditional Tornado Alley in recent years.

What causes tornadoes?

Tornadoes start with thunderstorms. Think of the thunderstorm as the parent of the tornado. When atmospheric conditions favor the development of severe storms, tornadoes can form.

The recipe for a tornado requires a few important ingredients: low-level heat and moisture and cold air aloft, coupled with a favorable wind field that increases in speed with height, as well as changes in the wind direction in the lower levels.

The right combination of heat, moisture and wind can develop rotating thunderstorms capable of spinning off a tornado or a tornado family. Thunderstorms capable of spinning off tornadoes typically develop along and ahead of a frontal boundary – where warm and cold air masses meet – often accompanied above by a strong jet stream.

Why do tornado outbreaks seem to be getting more frequent and intense? Is climate change playing a role?

Studies do show tornadoes getting more frequent, more intense and more likely to come in swarms.

The most intense and longest-lasting tornadoes tend to come from what are known as supercells – powerful rotating thunderstorms. The December 2021 outbreak, with more than 60 tornadoes that swept across Kentucky and neighboring states, came from a supercell. The 2011 outbreak in Alabama was another.

All of this unfolds under the umbrella of global warming. While it’s still hard for climate models to assess something as small as a tornado, they do project increases in severe weather.

What’s interesting is that despite that increase, the per capita death toll from tornadoes has actually gone down in the latter half of the past 100 years. So, as bad as these new outbreaks are, science and technology are saving lives at a faster rate than storms are killing people.

Scientists can now anticipate and forecast areas where tornadoes may develop. If you look at NOAA’s Storm Prediction Center website, you’ll see eight-day outlooks now. That’s based on scientific knowledge and technology able to target where conditions conducive to tornadoes are developing.

People also know what to do now and are more likely to get warnings, and more homes have safe rooms able to withstand a tornado. Social media also plays a big role today. A few years ago, I had a student who was on his family’s farm when he got a text warning that a tornado was coming. He and his family got to safety just before the tornado hit.

The Southeast seems to be getting a lot more severe storms. Has Tornado Alley shifted?

In 2016, my students and I published the first paper that clearly showed, statistically, the emergence of another center of tornado activity in the Southeast, centered around Alabama.

Oklahoma still has tornadoes, of course. But the statistical center has moved. Other research since then has found similar shifts.

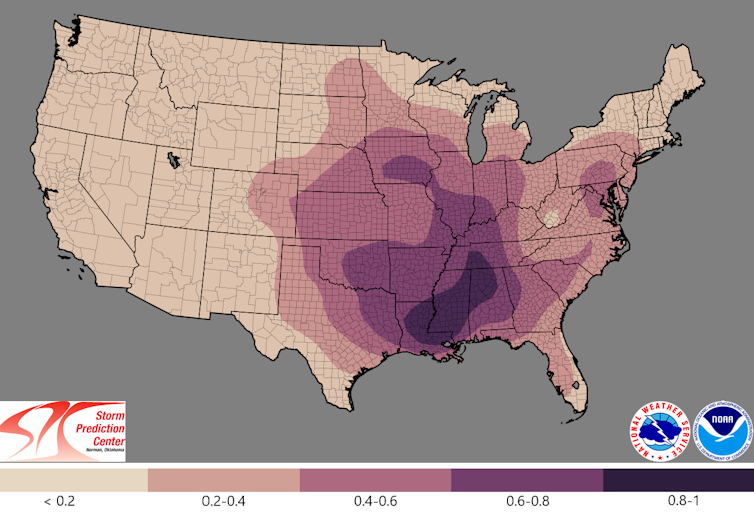

NOAA Storm Prediction Center

We found a notable decrease in both the total number of tornadoes and days with tornadoes in the traditional Tornado Alley in the central plains. At the same time, we found an increase in tornado numbers in what’s been dubbed Dixie Alley, extending from Mississippi through Tennessee and Kentucky into southern Indiana.

In the Great Plains, drier air in the western boundary of traditional Tornado Alley probably has something to do with the fact that tornadoes are a declining risk in Oklahoma while wildfire risk is growing.

Research by other scientists suggests that the dry line between the wetter Eastern U.S. and the drier Western U.S., historically around the 100th meridian, has shifted eastward by about 140 miles since the late 1800s. The dry line can be a boundary for convection – the rising of warm air and sinking of colder air that can fuel storms.

While scientists don’t have a full picture of the role climate change may be playing, we can certainly say we live in a warmer climate, and that a warming climate provides many of the ingredients for severe storms.

Ernest Agee, Professor Emeritus of Atmospheric Science, Purdue University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The Conversation is a nonprofit news source dedicated to spreading ideas and expertise from academia into the public discourse.