What is Giving Compass?

We connect donors to learning resources and ways to support community-led solutions. Learn more about us.

Search our Guide to Good

Start searching for your way to change the world.

As panelists attending the Funders Network conference in New Orleans discussed the resources for funding grassroots climate groups, a familiar message range true. Despite the plentiful local and global case studies of successful local efforts that are mitigating some of the worst impacts of climate change, funding of grassroots solutions remained underfunded and overlooked by mainstream philanthropy. According to Candid, “Most philanthropic climate change mitigation funding stays in the Global North promoting top-down approaches, with only 3.75 percent of funding going toward justice- and equity-oriented efforts.”

Calls from grassroots organizations like the Climate Justice Alliance, and funder networks such as Edge Funders Alliance, the CLIMA Fund, and the Regenerative Economies Organizing Collaborative (REO) echo the alarm that NCRP first sounded in its 2012 report, Cultivating the Grassroots. Principally authored by consultant and former Elias Foundation Program Officer Sarah Hansen, the report outlined the practical and moral need to shift resources to local communities and movements in the climate justice fight.

Hansen wrote that despite the increasing pace of social change around the world, the environment and climate movement was failing to “keep up with movements for justice and equality.” What, if anything, has changed since then?

What We Saw Then

NCRP research noted how in 2009, environmental organizations with budgets of more than $5 million received half of all contributions and grants made to all environmental organizations, despite comprising just 2 percent of environmental public charities.

“From 2007-2009, only 15 percent of environmental grant dollars were classified as benefitting marginalized communities, and only 11 percent were classified as advancing social justice strategies like policy change, advocacy, community organizing, and civic engagement. In the same time period, grant dollars donated by funders who committed more than 25 percent of their total dollars to the environment were three times less likely to be classified as benefitting marginalized groups than the grant dollars given by environmental funders in general.”

Hansen zeroed in on the fact that for all the increasing money invested in top-down approaches and funding of national groups, public policy on the issue had barely moved since the mid-1980s.

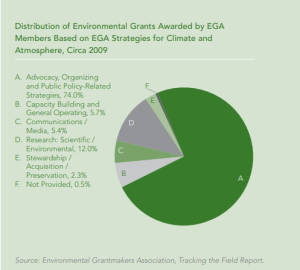

One of the stats cited in NCRP’s 2012 Report, Cultivating the Grassroots: A Winning Approach for Environment and Climate Funders.

“By engaging meaningfully at the grassroots level, grantmakers have the opportunity not just to support efforts that are especially strong but to use their work at the local level to build political pressure and mobilize for national change,” wrote Hansen. “Grassroots organizing is especially powerful where economic, social, political and environmental harms overlap to keep certain communities at the margins.”

The report included examples that evidenced the kind of high- impact, cost-effective grassroots organizing that grantmakers could fund towards a more just future. Case studies included looking at the work of Arizona’s Sky Island Alliance, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation’s New Constituencies for the Environment” (NCE) initiative and a look into Patagonia, Inc’s Environmental Initiatives with grassroots groups like Louisiana’s Bucket Brigade. It also included specific concrete suggestions for how environment and climate funders can engage with this vast potential constituency.

NCRP Executive Director Aaron Dorfman saw in the data a missed opportunity for the sector—to capitalize on the freedom to innovate which their size and wealth often brings.

Read the full article about grassroots climate justice work by Elbert Garcia at the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy.

Categories:

- Climate

- North America

- Philanthropy (Other)