Giving Compass' Take:

- Sarah Hillyer and Carolyn Spellings explain how the Global Disability Rights Map is used to advance the work of the Paralympics, Special Olympics, and Deaflympics.

- What role can you play in spreading the information and message behind this project? Are you ready to support disability rights in your country?

- Learn how philanthropy can incorporate disability rights in COVID-19 response.

What is Giving Compass?

We connect donors to learning resources and ways to support community-led solutions. Learn more about us.

When the Americans with Disabilities Act was signed into law in 1990, it became illegal to restrict access – to employment, education or federally funded institutions – based on disability. The ADA made it easier for wheelchair users, senior citizens or a disabled child to navigate public spaces and to have equal access to learning.

Many Americans who are not disabled benefit from the ADA. Building ramps, curb cuts, wider halls and audio instructions at crosswalks were a result of this law. The ADA made it easier for a parent to push a stroller down the sidewalk, to cross the street guided by aural prompts or for students with dyslexia to learn and excel in school.

December 3 is the United Nations International Day of Persons with Disabilities. While ADA protects the rights of Americans with disabilities, what protections exist around the globe? Are there policies that protect a child in Ethiopia born with hearing loss? Or the Venezuelan woman who lost the use of her legs in an automobile accident? What about a teenager in Senegal born with Down syndrome?

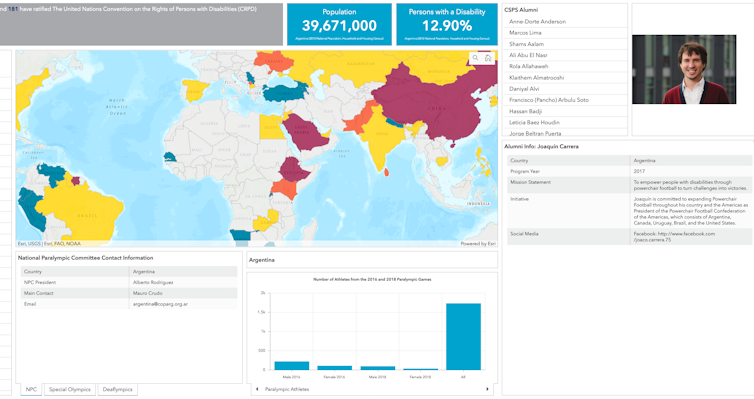

The University of Tennessee Center for Sport, Peace, and Society has created the Global Disability Rights Map, an interactive map that advocates for the rights of people with disabilities throughout the world. The map can also serve to empower those who want to create policies that protect people with disabilities.

Leveling the playing field

In 2016, JP Maunes, a disability rights advocate and sign language interpreter, and Adeline Dumapong, a Paralympic bronze medalist, both from the Philippines, sat in a Washington, D.C. restaurant riveted by the closed captioning technology on the television. For the millions of people who are deaf or hard of hearing, closed captioning provides information about what can be seen, even if it’s not possible to hear.

Neither Maunes nor Dumapong is deaf. Closed captioning, however, represented more than the convenience of being able to follow a sports commentary in a loud restaurant. They could see what was possible for people with disabilities in their own country. As Filipino citizens, Maunes and Dumapong wanted to know what they could do to bring attention to the discrimination against people with disabilities.

They had seen American athletes use their professional platforms to speak out against discrimination, unequal pay and sexual harassment, including Colin Kaepernick and Megan Rapinoe. How could they use their power as athletes to advocate for more inclusive laws and policies?

Changing the world through sports

Manues and Dumapong were participants in our program, the University of Tennessee Center for Sport, Peace, and Society, which has trained more than 80 athletes and professionals from 50 countries who work in the sports sector. Their questions, conversations with advocates around the world and the center’s work to promote the rights of people with disabilities led our team to create the Global Disability Rights Map.

Many people want to replicate the protections that ADA provides in their own communities. The center provides training on existing laws and policies. It also helps athletes to create sport-based initiatives and improve the lives of people with disabilities in their home countries.

The Global Disability Rights Map describes the laws and policies in a given country and connects them to the Paralympic Movement, a global effort to promote para sports and assist para athletes to achieve excellence in sport. The map also provides information to athlete activists on how to advocate for more inclusive rights.

There are websites dedicated to explaining national and international laws and policies protecting people with disabilities, such as the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. But there has never been an interactive global map that displays the rights of people with disabilities combined with information about the Paralympics, Special Olympics and Deaflympics.

sportandpeace.com

The map includes country-specific information about the national offices of the Paralympic Committee, Special Olympics and Deaflympics and statistics on a country’s participation in the two most recent international competitions. In addition, the map features a biographical sketch of a local athlete using sport as a tool to promote the rights of people with disabilities and to foster greater social inclusion.

Designed as an open source platform, the map allows users to update and add new information on laws and policies and new sports-based disability rights initiatives. Updates are submitted through the website and reviewed by center faculty for accuracy before appearing on the map.

Mapping rights around the world

One of the center’s goals is to facilitate stronger partnerships and better collaboration throughout the sport sector. For example, the International Paraplympic Committee is set to sign a historical cooperation agreement with the International Disability Alliance “to advance the rights of persons with disabilities and jointly commit to use parasport as a vehicle to drive the human rights agenda forward.” Parasports are sports played by persons with disabilities, both physical and intellectual. Our map shows visually how interdisciplinary efforts from government, Parasports and local initiatives can advance human rights.

People with disabilities face numerous barriers every day. Our work at the center helps to equip people to become advocates and break down these barriers. As we research obstacles facing people with disabilities, this map can act as a powerful tool to help strengthen these important human rights.

Sarah Hillyer, Director, Center for Sport, Peace, & Society, University of Tennessee and Carolyn Spellings, Chief of Evaluation, Research, and Accountability and Clinical Assistant Professor, University of Tennessee

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. The Conversation is a nonprofit news source dedicated to spreading ideas and expertise from academia into the public discourse.