What is Giving Compass?

We connect donors to learning resources and ways to support community-led solutions. Learn more about us.

Search our Guide to Good

Start searching for your way to change the world.

Giving Compass' Take:

• Data from the Prison Policy Initiative reveals trends in women's mass incarceration in 2019.

• How can this overview inform efforts to reduce mass incarceration? What does the incarceration of women look like in your state?

• Learn why we need to help women being released from prison.

With growing public attention to the problem of mass incarceration, people want to know about women’s experience with incarceration. How many women are held in prisons, jails, and other correctional facilities in the United States? And why are they there? How is their experience different from men’s? While these are important questions, finding those answers requires not only disentangling the country’s decentralized and overlapping criminal justice systems, but also unearthing the frustratingly hard to find and often altogether missing data on gender.

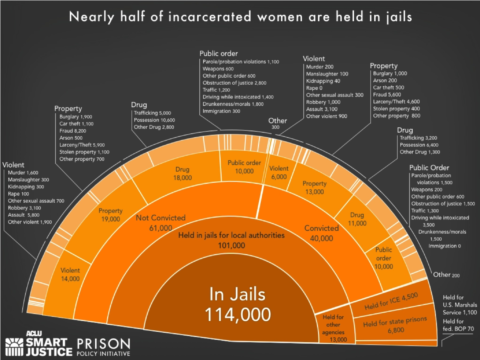

This report provides a detailed view of the 231,000 women and girls incarcerated in the United States, and how they fit into the even broader picture of correctional control. We pull together data from a number of government agencies and calculates the breakdown of women held by each correctional system by specific offense. The report, produced in collaboration with the ACLU’s Campaign for Smart Justice, answers the questions of why and where women are locked up.

In stark contrast to the total incarcerated population, where the state prison systems hold twice as many people as are held in jails, more incarcerated women are held in jails than in state prisons. As we will explain, the outsized role of jails has serious consequences for incarcerated women and their families.

Women’s incarceration has grown at twice the pace of men’s incarceration in recent decades, and has disproportionately been located in local jails. The data needed to explain exactly what happened, when, and why does not yet exist, not least because the data on women has long been obscured by the larger scale of men’s incarceration. Frustratingly, even as this report is updated every year, it is not a direct tool for tracking changes in women’s incarceration over time because we are forced to rely on the limited sources available, which are neither updated regularly nor always compatible across years.

Particularly in light of the scarcity of gender-specific data, the disaggregated numbers presented here are an important step to ensuring that women are not left behind in the effort to end mass incarceration.

Read the full article about women's mass incarceration in 2019 by Aleks Kajstura at Prison Policy Initiative.