What is Giving Compass?

We connect donors to learning resources and ways to support community-led solutions. Learn more about us.

Search our Guide to Good

Start searching for your way to change the world.

In the summer of 2020, NCRP published Black Funding Denied, a research brief that, using grant and Census data, measured grantmaking that explicitly benefitted Black people. It also focused on data from 25 of some of the country’s largest community foundations, which included funders in communities where NCRP had Black-led nonprofit allies and members. More than two years later, NCRP reflects on the growing philanthropic resources for Black communities; showing us that change is possible yet reminding us of the crisis it took to get there. This reflection illustrates for us what our sector needs for these new funds to incentivize actual structural change.

Following the murder of George Floyd in 2020, the Movement for Black Lives helped catalyze a historic national racial reckoning in almost every sector and institution in the United States. Of course, structural racism did not first harm or impact Black Americans in 2020. Police violence is a leading cause of death for young men in this country – killing about 1 in every 1,000 Black men. A report from the Washington Post found that although Black women account for 13 %of women in the U.S., they make up 20 percent of the women fatally shot by the police and 28 %of unarmed killings. However, on-the-ground organizing and extensive mainstream media coverage that year of nationwide protests led to individuals, social media, and institutions pouring new attention and resources into the movements that Black activists have been leading for generations.

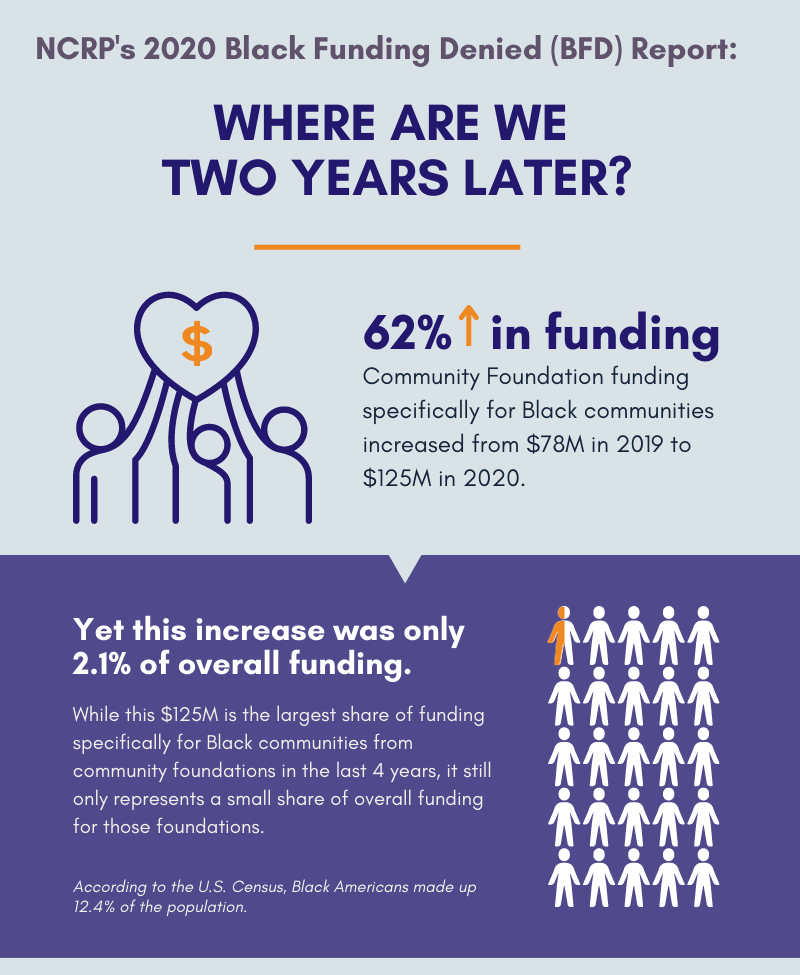

This work commanded philanthropy’s attention in new ways. We know now that in 2020, the 50 biggest public companies in America collectively committed at least $49 billion dollars. Philanthropist MacKenzie Scott alone is known to have donated at least $567 million to racial equity organizations. According to Candid’s [1] latest data, community foundations themselves granted $125 million to Black communities in 2020.

While all these financial contributions were a significant increase from previous years, this increased funding in many instances was short-term and not multi-year. The additional money in many cases has barely moved the needle for infrastructural and programmatic success for an already underfunded community that depends on foundation-based funding to survive an ever-politically unsure climate.

While all these financial contributions were a significant increase from previous years, this increased funding in many instances was short-term and not multi-year. The additional money in many cases has barely moved the needle for infrastructural and programmatic success for an already underfunded community that depends on foundation-based funding to survive an ever-politically unsure climate.

This is not a new conclusion and not a new ask from communities. Countless other reports have noted how if foundations are not targeting funding to specific BIPoC communities with racial equity expertise, then they are not doing enough to address the underlying conditions of structural racial injustice or inequity. As we have written often, past NCRP research and the lived experiences of a host of partners find that funders who specifically named these communities in their giving strategy were more likely to make progress against their equity goals and to hold themselves accountable.

NCRP has always sought to provide both grant makers and nonprofits with the kind of practical data and analysis that helps bridge the gap between funders’ best intentions and the reality of where their dollars go. That is why we published Black Funding Denied (BFD) at the end of the summer of 2020. Using grant and Census data, the research brief sought to report out the amount of grantmaking that some of the top community foundations were making to explicitly benefit Black people. The 25 foundations that we looked at not only represented a cross-section of some of the country’s largest community foundations, but also foundations in communities where NCRP has Black-led nonprofit allies.

More than two years later, how did our resource brief and subsequent engagement impact the conversation? What role did the community foundations we looked at play in growing philanthropic resources for Black communities?

Read the full article about funding for Black communities by Katherine Ponce at the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy.

Categories:

- North America

- Race and Ethnicity

- Philanthropy Research