What is Giving Compass?

We connect donors to learning resources and ways to support community-led solutions. Learn more about us.

Search our Guide to Good

Start searching for your way to change the world.

Count me among the disappointed to read the now-infamous memo written by former Google engineer, James Damore. The 10-page memo read more like a manifesto and described in detail how women, for reasons stemming from psychological and emotional differences to intellect, just aren’t up to the task of real engineering work. And that efforts to diversify the company were bad for business.

Google was right to quickly assess the situation, and publicly determine there was no place for such viewpoints in its organization. But lasting change will require more than removing a messenger. It’s the message that needs to evolve.

This divisive talk speaks to the pervasive, enduring and real power of stereotypes. No matter our steps forward, they stick like barnacles to the ways we educate girls and young people of color and how we hire and retain a diverse and competitive workforce.

In the tech sector, the impact is particularly pronounced. According to the National Center on Education Statistics, there were more than 500,000 open computing jobs this year but not nearly enough computer scientist graduates to fill them. And among those who are pursuing computer science degrees, just 28 percent are women. Think about all the jobs we could fill if we sent a message to women that they should pursue these careers.

When I started at Microsoft back in 1981 I hired one of our first female engineers. I also met my wife, Tricia, another Microsoft executive. She recently reminded me that in those early days of the company, we were a small group of young people working incredibly long hours and no one had time to be sexist. We were creating a new world in which we had so much faith.

Yet when we think back, the truth was there were few women in leadership and even fewer people of color at the company.

Those of us who come from that world believe it to be the vanguard of innovation and promise, shedding the stolid ideas from other business sectors. But the truth is, these pernicious stereotypes are everywhere and we can’t move past them if we don’t call them out, examine what’s underneath, and encourage a more thoughtful dialogue about race and gender. Even as Washington seeks to undercut programs like affirmative action, examples like Google highlight the need more public policy to incentivize diversity and expand opportunity.

Attitudes and beliefs about what people (who are not white men) can and cannot do start early. Because we tell them so, girls and young women come to believe they are just bad at math. Young people of color are sent messages that they are ‘troublemakers’ and that academic achievement just isn’t for them.

These messages often become self-fulfilling prophecies. Claude Steele articulates this theory – stereotype threat – in his book Whistling Vivaldi demonstrating just how insidious they can be – leading to, for example, normally high-achieving female math students performing worse than usual when they are reminded just before a test of their place in societal pecking order when it comes to math.

As I moved from the technology sector to philanthropy, equity has consumed much of my thinking. I’ve had to ask myself hard questions about the ways my own privilege has shielded me from the hard truths that non-dominant cultures face in this country and around the world.

The backlash against the conversation about equity – that it’s just political correctness run amok; that the people pointing these things out are just ‘snowflakes’ who need to stop whining – has only served to polarize the conversation in unhelpful ways.

The problem with this line of thinking is that it’s just flat out wrong. The truth is, striving for equity isn’t just morally correct, it’s economically smart. Diversity has been shown to increase market share for companies and create more qualified workforces. Racially diverse companies outperform industry norms by 35 percent. There are dozens of other positive economic outputs of diversity, equity and inclusion. But unless we instill – and implement – these values everywhere from the boardroom to the lunchroom, stereotype threat will persist. And individuals like James Damore will continue questioning why the environment that’s working perfectly for them needs to change.

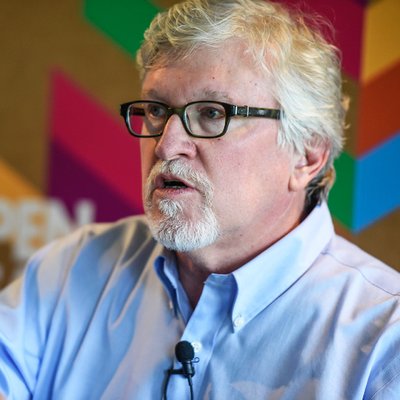

Jeff Raikes co-founded The Raikes Foundation with his wife Tricia Raikes. Jeff retired from his role as CEO of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation in 2014. He came to the philanthropic world from a 27-year career at Microsoft Corporation, where he was a member of the senior leadership team and president of the Microsoft Business Division. He serves on the boards of Costco Wholesale, the Jeffrey S. Raikes School of CS and Management at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, and the Microsoft Alumni Network. He is the Chair of Stanford University Board of Trustees. With Tricia Raikes he also co-founded Giving Compass and are on the advisory board at Giving Tech Labs.

Categories:

- North America

- Impact Philanthropy

- Gender Equity