What is Giving Compass?

We connect donors to learning resources and ways to support community-led solutions. Learn more about us.

Human Rights and Criminal Justice

From the right to life and liberty to freedom of expression, human rights are rights that every person across the globe is entitled to. In 1948, the UN issued the Universal Declaration of Human Rights to set a worldwide standard for human rights that all countries should adhere to. While the standard has not been achieved, it provides a framework for funders, governments, and NGOs to work within and build upon.

Specifically in the U.S., many individuals and organizations are working to ensure human rights are protected within the country’s criminal justice system. Because it’s large and complex, intersecting with racial equity, health, and families, among other things, there is still work to be done.

The U.S. has 5% of the world’s population, but holds almost 25% of the world’s prisoners. Mass incarceration, which leads to long sentences for minor offenses, is also linked to structural racism. These injustices represent massive losses for individuals, families, communities, and the country. This overview will help you better understand the areas in need of support.

What is Criminal Justice?

Criminal justice encompasses all stages of criminal proceedings and punishment. Police, courts, corrections, and parole all fall into this category. Criminal justice also extends to rehabilitation and support for victims' families. The effects of criminal justice methods have wide-ranging implications as each of the systems interact with each other and can affect society as a whole.

Data reveals that racial and gender disparities pervade the U.S. criminal justice system and these inequities have led to growing activism around the country. Black Lives Matter, a movement sparked by police shootings of black men, has drawn support from funders as well as pushback in the form of “All Lives Matter.” This issue is often framed as police vs. black communities, sparking tension. However, in some cases, the tension has turned to positive action where bridges have been built between the two groups.

Criminal justice reform was recently addressed at a federal level. Passed into law in 2018, the First Step Act was a successful bipartisan effort aimed at reducing recidivism and mandatory minimums, keeping prisoners closer to home, and improving data collection. This legislative progress represents hope for future reform and demonstrates that a controversial issue can be addressed through compromise and common ground.

Other criminal justice reform efforts include addressing police practices, jail overcrowding, prison education access, and services for formerly incarcerated people. These are all areas where funders can play a key role.

Why Should Donors Care About Criminal Justice Reform?

The criminal justice system affects more lives than most of us may realize. Research finds that 45% of the U.S. population has a close family member who has been incarcerated. Additionally, certain treatment before, during, and after an individual’s sentence affects health, education opportunities, and civic participation. Incarceration can also impact lifetime earnings for individuals, particularly for people of color. Family members are affected as well. For instance, having an incarcerated parent is considered an adverse childhood experience, which is linked to disease and other challenges later in life.

Mass incarceration, a product of structural racism and part of the “tough on crime” approach, has dramatic implications for racial justice and equity in this country. Rooted in fears about the progress of the civil rights movement and the changing employment landscape in the 1980s, mass incarceration exposes how punishments are harsher and racially disparate for Black people. Racial bias in the judicial system, including juries, is another factor plaguing the criminal justice system.

Mass incarceration is also expensive for the government. As the prison population grows, so does the cost of maintaining that population. This money comes from tax-payers and could be used for other causes, including preventive solutions for criminal justice. Data from The Hamilton Project and Brookings demonstrates this relationship:

The costs of the current criminal justice system - on individuals, families, and communities - demonstrates the need for immediate and sustained action on the part of activists, nonprofits, policymakers, and funders.

Criminal justice is an issue everywhere - but it looks a bit different everywhere. Variations in state and local criminal justice laws and practices mean that funders who want to address this issue should start by learning about incarceration in their city and/or their state.

Seven Facts About Jail in 2019

The Arrest, Release, Repeat report from the Prison Policy Initiative examines U.S. county jails. The overarching trend is that low-income people are more likely to go to jail, and previous bookings increase the likelihood of future bookings.

- At least 4.9 million people are arrested and booked in jail every year.

- At least 1 in 4 people who go to jail in a given year will return to jail over the course of a year.

- At least 428,000 people will go to jail three or more times over the course of a year – the first national estimate of a population often referred to as “frequent utilizers.”

- 49% of people with multiple arrests in the past year had annual incomes below $10,000, compared to 36% of people arrested only once and 21% of people with no arrests.

- Despite making up only 13% of the general population, Black men and women account for 21% of people who were arrested just once and 28% of people arrested multiple times.

- People with multiple arrests are much more likely than the general public to suffer from substance use disorders and other illnesses, and much less likely to have access to health care.

- The vast majority of people with multiple arrests are jailed for nonviolent offenses such as drug possession, theft, or trespassing.

Entering the Criminal Justice System

Police: Police are often the first encounter individuals have with the criminal justice system. Public trust in police has disintegrated particularly as more data emerges about racial discrimination toward individuals, including through stop-and-frisk policies. Police also have a presence in some schools and students, particularly students of color, who experience aggressive policing can see lower grades and harsher discipline. In addition, data shows that suspensions and expulsions are linked to the school-to-prison pipeline.

Bail and Pretrial Detention: There is risk for mistreatment and excessive detention once individuals enter the criminal justice system. Cash bail, the system of detaining people who have not been convicted of a crime unless they pay a set amount of money, is a significant obstacle for low-income people. Unaffordable bail and subsequent pretrial detention has massive consequences for detainees and their children as they are separated from each other and living situations are disrupted. Pretrial detention can have negative implications for court appearances, conviction, sentencing, and future involvement with the justice system. It’s more likely to impact people of color and low-income people, and fails to improve court appearance compliance, the supposed purpose of the practice.

However, there is good news. There is a significant, ongoing movement to end unaffordable cash bail and reduce pretrial detention for those who pose no threat to others. While changing laws around bail and pretrial detention is ideal, New York judges and decision-makers have chosen to forgo bail in order to make a difference.

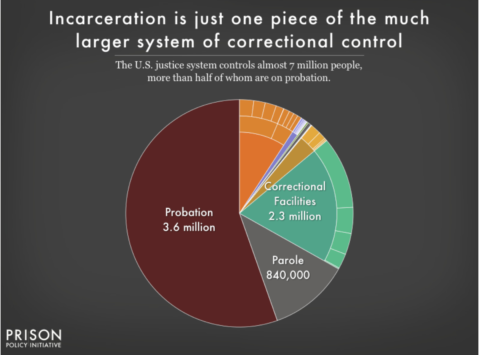

Mass Incarceration: The origin of mass incarceration stems from the movement to get “tough on crime.” Pretrial detention, mandatory minimums, and many other factors conspire to feed the sky-high mass incarceration numbers in the United States:

Despite its longevity, mass incarceration isn’t working. A Justice Strategies/Harvard study showed that over 10 years, serious crime in NYC fell by 58% while the incarceration rate decreased by 55%. This trend is reflected across the country. Advocates for reform argue that a focus on safety (community supervision, rehabilitation, etc.) is needed instead. Indeed, mass incarceration hurts public health and increases drug-related deaths. Mass incarceration also keeps children from their parents, which causes stress within families. Activists are calling for an end to this practice and demanding a focus on providing employment opportunities and resources to live life fully after prison.

If mass incarceration isn’t effective, why does it still exist? Private prisons have profit incentives to keep the prison population high and their own costs low by providing as few services as possible. Private prisons are also associated with longer prison sentences.

Life During Imprisonment

Life in jail and prison is restrictive. Even the most basic human needs for hygiene and sanitation - like tampons and pads - may not be provided. These necessities must be purchased at an inflated cost by detainees who have no or little income or savings. The divide between those who have money and those who do not represents a significant gap in lifestyle. Simple things like phone calls, video calls, and emails - cheap or free outside of prison - can carry high costs for prisoners. In-person visits are sometimes restricted, isolating prisoners from their families. These practices reduce or eliminate contact with the outside world that could help them reintegrate after incarceration. There are also health risks associated with prison. Transportation, solitary confinement, and drug overdoses threaten the health of prisoners.

Preparing for Release

Education is one to prepare inmates for life outside. Teachers can turn a prison into an opportunity for educational advancement. Federal programs can increase access to secondary education in prisons. Existing programs are insufficient to serve the prison population, but they offer a strong foundation. Interventions focusing on increasing access to educational materials and supports can fill the gaps left by prisons. Funders can also bolster education programs through private donations.

Life After Imprisonment

Incarceration doesn’t end with release from prison:

The significant population of parolees is cause for concern, considering we don’t know how effective parole is. Parole violations are also a significant contributor to mass incarceration as many parolees return to prison after technical violations:

The unemployment rate for formerly incarcerated people is more than 27% because obstacles - stigma or lack of recent work history - make re-entry to the workforce difficult. Educational programs in prisons can help to reduce this number. Some organizations work to address this gap by specifically hiring formerly incarcerated people to help them earn a living and get job experience.

Upon release, formerly incarcerated people sometimes receive gate money intended to help them get back on their feet. These funds are usually insufficient to help them reach their families, find housing, buy clothing, or cover any number of essential purchases they may need to make.

Formerly incarcerated people also face difficulties accessing healthcare, education, and stable housing. For example, young adults who experienced the school-to-prison pipeline often lack a high-school diploma and former inmates are ineligible for Pell grants and federal student loans. The combination of these factors makes it very difficult for formerly incarcerated people to attain the level of education they need to access employment opportunities. They also often lack the support they need to recover from the trauma of prison. According to New Profit, more than half of returning citizens are unemployed one year after their release from prison, and partly as a result, more than 70 percent return to prison within five years.

For returning citizens who have been in prison for a long time, it can be difficult to reconnect with their family or community. Providing supports for these people can help them to successfully transition into life outside of prison, reduce recidivism, and increase productivity.

Policy:

Experiments that could lead to evidence-based reforms are already happening around the country. For example, the San Joaquin County has become a lab for prison reform in California. Here are a few other examples of policy-driven efforts:

- Find out how Michigan can reduce its massive incarcerated population.

- See what other states can learn from New Jersey’s bail reform success.

- Explore how public health insurance can close the health coverage gap for formerly incarcerated people.

There are opportunities to improve criminal justice in every state through policy. Open Philanthropy Project provides an overview of its criminal justice reform strategy which can be broadly applied. Read about criminal justice reforms to watch.

Race, Gender, and Sexual Orientation:

Not everyone experiences the criminal justice system in the same ways. Race, gender, and sexual orientation can shape the experiences we have with the criminal justice systems.

Black and Latino boys suffer specific consequences of police stops, even when those stops don’t end in disaster. Although women of color face racial profiling from police, they are often left out of the national conversation about policing methods.

This bias is not limited to the police, inequities throughout the criminal justice system mirror and amplify inequities in society. People of color are more likely to receive pretrial detention. Gendered and heteronormative policies prevent queer women from successfully reentering society. Queer people and Latinx people suffer the impacts of mass incarceration disproportionately. There is not even enough data about Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the criminal justice system to draw strong conclusions about its impact on this group.

A lack of data makes it difficult to paint a full picture of women’s incarceration as well. The information available indicates that while there has been progress against mass incarceration, it has been largely limited to men.

Who You Should Know:

There are many organizations working hard to reveal the realities of the criminal justice system in the United States and improve it. Here is a short list to get you started:

- The Marshall Project is a criminal justice news source covering both personal and political stories in the United States.

- Prison Policy Institute uses data to advocate for the end of over-criminalization in the United States.

- Open Philanthropy Project is a leading funder of criminal justice reform work and provides strategy and grant recommendations to others.

- Vera Institute of Justice works directly with governments to improve criminal justice as part of their mission to advance racial justice.

- Ford Foundation has a track record of addressing criminal justice in the United States as part of their racial equity efforts.

- New Profit works with social entrepreneurs, philanthropists, and other changemakers to break down barriers to opportunity in America.

- National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy promotes philanthropy that serves the public good and is responsive to people and communities with the least wealth and opportunity.

How Can I Get Involved With Criminal Justice?

Just as there are many elements to criminal justice, there are many ways for funders to get involved. Your own approach should be shaped by your specific goals, geographical considerations, and budget.

Advocacy: Supporting legislation is an effective way to make an impact on criminal justice reform at scale. It is important to remember that advocacy can take place at all levels of government. Issues that can be addressed include: mass incarceration, jail overcrowding, and solitary confinement.

Legal Action: The Seattle Foundation, in partnership with the ACLU of Washington and Disability Rights Washington, has increased access to mental health services for incarcerated people in Washington State through a legal settlement. This approach can force governing bodies to fulfill their legal obligations to prisoners.

Social Enterprise: Help to address the employment difficulties that formerly incarcerated people face by supporting social enterprises that employ them. There are programs and businesses across the country that are already working through this vehicle.

Funding: You can fund organizations that provide a range of services aimed at helping people who are impacted by the criminal justice system. Funding grassroots organizations like Black Lives Matter is an impactful way to address the issues around racial bias in the criminal justice system and beyond. Funders can also target specific problems like racist algorithms that negatively affect people of color in the system. Supporting overarching services for formerly incarcerated people can help to reduce recidivism.

Where to Give to Support Criminal Justice:

Donating to philanthropic issue funds is a great way for donors to leverage the knowledge of experts to make an impact on an issue. Giving Compass vets funds to help donors quickly and easily identify high-impact opportunities to tackle an issue. In the area of criminal justice, Life Comes From It fund, The National Council for Incarcerated & Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls fund, the Art for Justice Fund and the Unlocked Futures Fund are opportunities for donors to confidently give to make an impact. Life Comes From It is a first of its kind grantmaking circle where decisions over funding are made by people heavily steeped in restorative justice, transformative justice, and indigenous peacemaking. The National Council for Incarcerated & Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls creates organizing spaces for neighborhood-led infrastructure and systems for community accountability, economic, and personal development all led by the most directly impacted women and girls from the community. The Art for Justice Fund was seeded by the sale of a painting from Agnes Gund’s art collection. The fund works to reduce mass incarceration. The Unlocked Futures Fund provides financial backing to entrepreneurs who have been directly impacted by the criminal justice system.

Related Criminal Justice Articles:

- Why It’s a Crime to Be Poor in America: Global Citizens examines America’s criminal justice system and explains the unfair position poor Americans are put in when accused of a crime, guilty or not.

- Disrupting the School-to-prison Pipeline by Reducing Suspensions: California is addressing the school-to-prison pipeline by trying to reduce suspensions through less-punitive punishment tactics.

- 6 Myths About Cash Bail Reform: Daniele Selby debunks six myths about cash bail reform, focusing on why eliminating the system would not be harmful to communities.

- The Reframing of Mass Incarceration and the Right to Vote: Ruth McCambridge reports that as a nation we are facing a mass incarceration crisis that destroys families and communities.

- How Formerly Incarcerated People Can Get Back on Course: This report from the Prison Policy Initiative shows the depth of educational exclusion among formerly incarcerated people — and discusses ways to make a course correction.

From connecting inmates to educational opportunities to restoring the voice (and vote) of returning citizens, there is no shortage of opportunities to make an impact on the current criminal justice system. Donors should consider the best route to long-term change, but a few paths to effectiveness include being intentional about removing barriers and supporting community building.